|

I returned from a trip to Los Angeles yesterday morning on a (unplanned for) red-eye flight, slightly bedraggled, but feeling the happy after-glow of a good vacation.

And good it was, though it started off somewhat inauspiciously, in that my March 22 Columbus-LA flight turned out to be somewhat eventful. I guess the heart of the problem was the airlines' current occasional practice of seating families apart, the rationale being that if you want seats next to each other you must pay extra for the service. Tacky, right? People have been protesting the practice, but maybe not yet loud enough. Anyway, it was spring break week so it shouldn’t have come as a complete surprise that our flight to LA was full of kids: crying babies, plugged-in teenagers and every variety of little and big kid in between, most of them attached to one or more parental units. Except for the four kids in the back of the plane who were flying unaccompanied: two sitting next to me on the left and two sitting across the aisle from me on the right. So it was four kids and one adult. Can you envision the potential dynamic? On my left were two sisters, one looked about 9, the other I'd guess maybe 13. We made friends over my shared Combos, and I learned that they were traveling from Columbus to LA to spend spring break with their grandmother. It was their first visit to Los Angeles and their first time flying alone. They were quietly excited and I thought, a little nervous, but pleasant enough traveling companions. Alas, the two little wild things across the aisle were another story altogether. They were a brother and sister, the little girl was 6 and the little boy 7, on their way from Columbus where they live with their mother to visit their father who lives in Los Angeles. Immediately bored and wired, they were at it before the plane left the ground, yelling, shrieking, trying out every conceivable sound or noise they could blast out of their little lungs, annoying each other, hitting each other, throwing around their backpacks and the pile of toys, blankets, books, crayons, and other diversions they'd hauled along, standing on the seat and pressing the attendant call button, and, of course, sucking up the attention of everybody around them. Except, at least for about the first hour, me. Now, avoiding engagement with these kids for even an hour was no small feat on my part. I mean, being the adult sitting directly across from them I was the obvious target, right? But I refused to engage. "No," I thought to myself. Because I knew that the moment I responded to them I'd have ownership of them for the rest of the trip. "No," I repeated to myself, closing my eyes and pretending to sleep while they tried to get my attention. After all, I'd paid the airline almost $500 for this plane ticket and for that price I didn't feel like babysitting. It was the airline that allowed these two little whirling dervishes to fly alone, let the flight staff take care of them. And the flight staff did for a while. At first one flight attendant or another was rushing over to them every two minutes; after a while the flight attendants started ignoring them, much to my dismay; because that's when they started doing a full-court press on me. I finally caved when the little girl wouldn't cease poking my arm. I turned to her and noticed that she had an angry purplish welt next to her eye that looked fresh. When I asked her where she got it she showed me the seat-belt buckle and told me that her brother had just hit her in the face with it. Then she proceeded to roll up her pant leg and show me all the other bruises her brother had recently inflicted on her, which caused her brother to scream at her for telling. At that point, as I had foreseen, I was pulled in. And by the time I calmed that crisis and the next one when the little girl thought she'd lost the metal washer with a string through it that she called her necklace, it was clear that for the next four hours I was to be the designated adult. When the little girl threw her backpack out into the aisle the flight attendant informed me that it belonged under her seat. While the little girl was pulling off her identification wristband the nice little girl on the other side of me informed me that the little girl shouldn't pull off her wrist band because she'd need it to get matched up with her father. When the two kids managed to pull the hard plastic covering off the armrest of one of the seats I decided to just stick it under a seat until an attendant came by. But the man sitting behind the kids shot me a disapproving look as he retrieved the broken piece of cover forced it back onto the armrest. I was obviously doing a second-rate job of keeping my charges in line. I did get one perk from the whole deal: at one point the girl sang for me "The Boogie-Woogie Bugle Boy Of Company B" - the whole song! Word- and note-perfect! She did have an amazing voice for a 6-year-old, and she said she could sing "Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Heart's Club Band" and other songs, too, which I would like to have heard, but, alas, after "Bugle Boy" she was done singing and it was back to fighting with her brother. In the end I felt sorry for these two kids. But then it does seem that even kids who start out wild mostly manage to grow up into more or less functioning adults who end up reproducing some wild kids of their own. Still, after this heckacious flight I came to a very firm conclusion: No way should parents or airlines allow young children to fly alone. Especially on the same plane as me.

1 Comment

"The Mustard Seed" was inspired by the story my mother often told me of the death of her sister Rosemary a few days after Rosemary's 4th or 5th birthday, my mother can no longer exactly remember, though it seems to me that when she used to tell me the story she said that Rosemary was just 4 when she died. Based her mother's description my mother, a nurse, believes that her sister died of some form of bacterial meningitis. I made up the character of Josie, though I based her on my mother, who did use to deliver the laundry for her mother. But my mother was only 2 years old when Rosemary died, so she remembers the story only as it was told to her by her mother. Some of the details of the story came directly from what my mother told me: -That my grandmother found Rosemary sitting on the front stoop on her fourth or fifth birthday, which she pronounced "bursday", holding a bag of jimmies, waiting for her cake. -That my grandmother's customers were often lax about paying her and so she couldn't cobble together enough money for the ingredients for a birthday cake for Rosemary. -That as Rosemary lay dying she did see a vision, which she described to her mother. After Rosemary's death, the second of her children to die, my grandmother fell into a severe depression. She believed that all her children were going to die and that she was helpless to save them. It was a neighbor woman who came to my grandmother's rescue, lending a hand with the housework and childcare while talking her through her sorrow. And so my grandmother recovered. I've always believed that this story from her early childhood is the key to my mother. I believe it explains so much about her: her desire to enter a healing profession, how she could never stand to see anyone unhappy, how she takes the world's suffering to heart. And her love of eating and feeding others. Sometimes I think this story is the key to me, too. In a comment from a couple of days ago my sister Romaine asked why I developed an interest at this time in Florence Fey's life story. The answer is that I've always felt captivated by the story of this grandmother of ours whom we hardly knew. Ever since I wrote "The Mustard Seed" I always thought about someday writing down the rest of what I knew of her story. And by way of this blog that someday finally came. I wrote this story about 20 years ago and submitted it to a short story contest sponsored by the The Catholic Times. I won the contest and $50.

It's based on a true story story from my grandmother's life that my mother told me many times when I was growing up. The Mustard Seed Twelve-year-old Josie Foy trudged up the block dragging behind her a large wagon piled high with stale laundry. It was no more than the usual Saturday load, but today her arms ached as if she were pulling the weight of all the world's lost hope. As she rounded the corner and caught sight of little Peggy playing on the cracked front stoop her heart was gripped with a pang of aching love. Josie pulled the wagon to a halt against the stoop then sat down and took Peggy on her lap. "Whatcha got there, Pix?" she asked, kissing her sister's warm rosy cheek and brushing back a wisp of the child's angel-fine hair. Peggy unrolled the top of the small paper bag she'd been holding. "Ooooh, chocolate jimmies for Peggy!" Josie exclaimed. "For my bursday cake, Dosie! Today I'm four!" Josie swallowed hard. "So you are, Pix." Peggy squirmed from her sister's lap, grinning in delight. She hopped off the stoop and began rummaging through the laundry wagon. "Did you bring Peggy's cake, Dosie? For my bursday?" Josie felt a tightening in the back of her throat. She stood up, then stepped over to the wagon and hoisted a heavy bundle of laundry. "No, Pix," she sighed, "not yet." "Soon, Dosie?" Peggy's pixie-blue eyes shone with happy expectation. "Yes, soon," Josie whispered, choking back tears as she dragged her burden up the steps and through the front door. "You're a good girl, Josie, you didn't tarry today, thank the Lord!" Josie's mother grabbed her patched sweater and purse, then glanced distractedly at their small kitchen clock. "Little Peggy's been in a state all morning over her cake. I'll bring her back a peppermint stick, as well, and one for you. Quick, then, Josie, the money." But Josie only hung her head and began sniffling. Mrs. Foy's eyes widened in dismay. "Dear Mother in Heaven, Josie! Please don't tell me you've not been paid again! Oh please, Josie, not today, not with Peggy's birthday!" But it was true. Though Josie had spent her entire morning exchanging this week's batches of clean and freshly pressed laundry for next week's, not one of her mother's customers had paid her today. "Oh, why, why!" cried Mrs. Foy, burying her head in her hands. But she knew why as well as anyone, for in the depths of the Depression it was becoming more and more the practice to put off paying the less pressing debts. Josie watched through a film of tears as her mother rushed around the kitchen rummaging through drawers and cupboards, searching for the stray penny, the forgotten nickel. And for her efforts Mrs. Foy soon held in her palm six cents. Enough for a loaf of bread or a small bag of rice. But nowhere near enough for the butter, eggs, and sugar needed to make a cake. Just then Peggy skipped through the front door. "Is my bursday cake here?" she chirped. Mrs. Foy looked at her daughter and shook her head slowly, her eyes filling with helpless tears. Josie knelt down to her sister and hugged the child tenderly. "Soon, Pix," she sadly promised. "Soon." But the following day was Sunday and it took Mrs. Foy another two days of begging door-to-door for her wages before she was able to give Peggy her birthday cake. And by then it was too late. For by then the fever had set in, and though Josie and her mother coaxed and wheedled, Peggy had no interest in tasting her cake as she slipped back and forth between glassy-eyed wakefulness and fitful sleep. Of course the child needed a doctor, but who had the money? Josie and her mother took turns sitting by Peggy's bed, helplessly watching her worsen in spite of their cool damp cloths and constant anxious prayers. And it was in the early hours when not even a sip of water could be forced through Peggy's colorless lips that Mrs. Foy rushed from the house to find a doctor and beg for the life of her child. Josie meanwhile knelt over the bed, her head buried in her sister's small rigid shoulder, her tears soaking the bedclothes. "Oh, please, Mother Mary," she sobbed and prayed, "Pix never even had her cake. Please, Blessed Mother, a cake with jimmies, it's all she wanted, don't take her yet!" "Dosie?" the weak whisper startled Josie out of her prayer. Peggy's eyes were burning brightly above a pale, strengthless smile. "I'm going ...to my bursday, Dosie." The child paused for a pained breath. "With her." "Wh-who, Pix?" Josie asked, lifting her head in amazed confusion, rubbing her eyes with the back of her sleeve. "The lady. In the blue dress. With no shoes. She's taking me, Dosie. To my bursday. To my cake. You'll come, too, Dosie, soon. The lady says." Josie stared at her sister for one wild-eyed, uncomprehending moment. But then she knew, for in the next moment she, too, felt the presence there in the room, hovering gently above them both. "Wait, Peggy, oh wait," she cried, rushing off to the kitchen for the gay little chocolate-sprinkled cake. "Here, Pix," she whispered lovingly, kneeling next to her sister's face, "take your cake with you." If the doctor had returned and entered the bedroom with Mrs. Foy perhaps he, too, would have witnessed the moment. But as it was, only she saw the vision of her two children caressed in the wide arms of the lovely lady draped to her bare feet in sky blue. The vision lasted only half a heartbeat, and had already ascended back to its source in the time it took for their mother to cry out and fall to her knees. Josie rose slowly from the side of the bed. "It's all right, Mama," she said softly. "Peggy's fine now." "Yes," her mother whispered. And as the sun rose that morning on tears of worldly sorrow and heavenly faith, one more soul shed its cocoon and rose on delicate wings to the realms of eternal delight. In the telling of her own story my mother always emphasizes that as a child she was happy; life as she knew it was good, though from a young age she had to do housework and care for her younger siblings while her mother worked, as well as help her mother with the laundry she'd bring home at night. My mother, always happy-go-lucky herself even now at 93 years old, describes her mother, despite her hard life and many sorrows, as both gentle and strong and, despite her hard life and many sorrows, resilient and fun-loving at heart, whatever meager fun there was to be found. From what little money my grandmother brought in each week she always saved a small amount. This was to provide for future tuition for secretarial school for my mother. My grandmother had decided that her son Gene would be on his own and her other daughter Mary would always need someone to take care of her; but for my mother she had a plan: that my mother would be a working woman who would have a good job that would enable her to take care of herself. Year after year, however great the family's need, my grandmother Florence's savings for her daughter were never touched. But when my mother graduated from high school and the time had come for her to apply to secretarial school she refused; she had decided that she wanted to become a nurse.  My favorite photo of my beautiful mother, Romaine, 23 years old, taken around Christmas of 1943 at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, where she served as an Army nurse during World War II  My second favorite photo of my mother, taken three years ago when she was 90 years old. I could continue the telling of my grandmother Florence Lubignac Fey's story as it unrolled through the lives of her children, and continues to unroll through the lives of her grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great grandchildren; but in truth those are other people's stories.

But my grandmother Florence Fey lived see her two able children prosper and her disabled child well-provided for. She saw her grandchildren born into freedom from want, into lives blossoming with opportunity. I'll end by saying that growing up I never got to know my grandmother Florence well, my grandfather Nick even less, though they lived in Scranton and we lived 125 miles away in Philadelphia. Extended families sometimes have their own politics and social orders. But through my mother I know something of their story. Tomorrow's post will be a short story I wrote about 20 years ago based on a chapter in my grandmother's life. After reading my sister Romaine's comment that my grandmother Florence's parents at one point came back for her I called my mother yesterday to ask her about it.

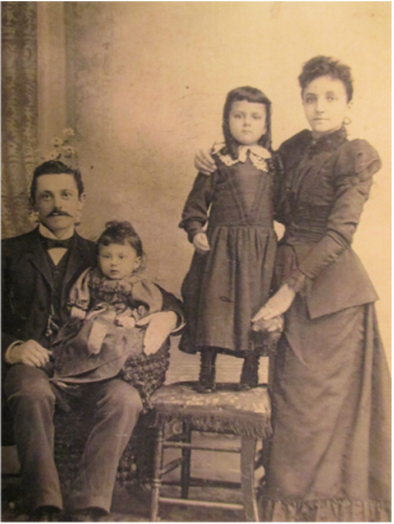

My mother said that, yes , her mother did tell her that her father once came to take her back. One day sometime before before the Lubignac's fled to Kentucky Pierre showed up at Nanny Stanton's door to take Florence home. And Florence wanted with all her heart to leave Nanny Stanton's and go back to her own family. But she was so angry at her parents and so hurt that they gave her away that she refused to go with her father, who then left without her. I wonder if Florence's refusal to go with her father was just the acting out of a childish wish to punish her parents? I wonder if she was holding out for her father to coax her, to make her go so that she could hold on to her anger until she was ready to let it go? Did she believe that her father would surely come back for her again and that next time, though still making her displeasure known, she would agree to leave with him? But her father never again came back for her. And as he walked away from his daughter for the last time did Pierre Lubignac feel his sorrow mixed with some portion of relief? Who can know? When it comes to our feelings we human beings can be so gray and conflicted, so twisted around our emotions that in our minds we can barely find our way from point A to point B. Who among us has never at one time or another ruminated over and over again over what we should have done? But to me there is one grand irony to this story, and it's this; When 9-year-old Florence Lubignac was, in my mother's words, being passed around like a playing card, she had no voice in her fate; what she wanted was not factored in, either by her fraught parents or by self-serving Nanny Stanton. And yet this time, when her father should have been as firm in taking her home as he'd been in giving her away, when Nanny Stanton should have cast her back as aggressively as she'd reeled her in, all the adults stood weakly or selfishly by and put upon this child the burden of making a decision that should not have been hers to make. Of course who knows if, for all the hardship she suffered, Florence didn't end up better off as Nanny Stanton's ill-used servant than she might have in her own unstable family? Who knows? Still, as my grandmother told my mother many times, "I would never give up one of my children. Not if I were down to my last crust of bread. My grandmother told my mother that she believed that her mother Virginia Lubignac ended up in a mental institution over the grief and remorse she suffered for giving away her daughter. I believe it, too. To be continued... NB: I'm in Los Angeles this week so my posts will pop up about three hours later than usual!  My father's parents, Joe and Violet Rupp, on their honeymoon. When my grandfather Rupp was young he once witnessed a blacksmith hitting a young man. The young man was the blacksmith's son, who turned out to be my grandfather Nick Fey. Continued from yesterday...

Was my grandmother Florence happy in her arranged marriage to my grandfather Nick Fey? Was he happy? I asked this question of my mother, to which she replied, cryptically, "Things were hard." Nick Fey was a blacksmith trained by his father, also a blacksmith, a harsh, mean-tempered man who expected his son to work for him without pay in return for his training. In a strange turn of events, my great-grandfather Rupp on my father's side was a customer of my great-grandfather Fey. One time my great-grandfather Rupp and his son (my father's father) were waiting in the blacksmith's shop and saw my great-grandfather Fey in a fit of anger hit his son and throw him across the room. When he was young my grandfather Nick was a talented violinist and mandolinist but he had to give up his music due to a loss of hearing that began in early adulthood. (The question has been brought up whether his deafness could have been the result of a blow to the ears by his father). Nick Fey appeared to have inherited his father's bad temper and impatience; he blew up frequently and unexpectedly, though he struck Florence only infrequently and was filled with regret afterwards. My patient grandmother, however, always attributed his anger problems to the unbearable, unending ringing in his ears that he swore was driving him crazy. Neither having any family support, my grandparents started their life together poor. There was one time when they were newly married that they had nothing to eat all day but one rutabaga (a turnip-like vegetable) between them. But my grandfather got a job as a metalsmith on the Erie-Lackawana railroad for $20 a week and my grandmother as a scrub-woman who worked eight hours for $1.50 a day then took her customer's laundry home at night for no extra pay. They were the working poor of their day. Whenever my mother told me stories of her childhood she generally spoke only of her mother, brother, and sister; of her father she spoke only rarely, for which reason I always thought that he must have been someone who came and went and that my grandmother was raising her children alone. When I finally asked my mother what role her father played in her life she told me that her father did live at home with them; it was just that he was deaf and so they couldn't talk to him even in his stable moods, and for this reason their mother was the meaningful presence in their life. My grandparents had five children, though two of them died: one a 2-year-old named Geraldine, the other a 5-year-old name Rosemary, both from illnesses that were never clearly diagnosed, though my mother, a nurse, suspects that the 5-year-old died of spinal meningitis. After the death of her second child, Rosemary, my grandmother sunk into a depression that was healed only with time and the need to care for her other children. Her remaining children were my mother, Romaine; my Aunt Mary who, born at home at 3 pounds, survived but was mentally disabled; and my Uncle Gene. My mother and her siblings grew up poor and, when the depression set in and there was no more work for their father, sometimes hungry. Still, my grandmother worked and there was always some food on the table, though for years the family's meals were a bowl of rice and milk for lunch and bread and coffee for supper. When they could afford it there was chicken once a week for Sunday dinner. To be continued.... I'm the granddaughter of a slave.

When she was 9 years old my mother's mother was sold into slavery by her parents not for money but for the implied promise that their daughter at least wouldn't starve. My grandmother Florence Fey was born in 1896 in Taylor, an affluent suburb of Scranton, Pennsylvania. Her father was Pierre Lubignac, a wealthy French businessman who emigrated from Paris to Canada in the late 19th century, and from Canada to the United States where he settled with his wife Virginia in Taylor and where he became a joint owner with two other men of a silk mill, probably the Victoria Silk Mill. Pierre, Virgina, and their six children lived in a palacial home with five servants, a Saint Bernard, and a fish pond on the grounds. Pierre was a profligate spender, showering his wife and children with gifts and regularly replacing the home decor with the best and newest of everything. It was a household of privilege and plenty. But the talent that Pierre Lubignac had for spending money he lacked in running a business. I don't know the exact details of how he went bankrupt: either the business was mismanaged and run into the ground, or he was fleeced by his two co-owners, or there was some other disastrous event or series of events; in any case, he lost everything and his family, once rich, became destitute. It would have been around 1905 when one of the Lubignac's former maids desired to enter the convent, but the woman's mother refused to let her go. Her mother, a hard woman whose name was Nanny Stanton, was a widow raising the four children of her other daughter who'd recently died in childbirth. Nanny Stanton would not allow this daughter to leave home because she needed her help with the childcare and endless household chores. I don't know exactly how it came about, but it came about that Nanny Stanton's daughter was finally permitted by her mother to enter the convent because she'd found a replacement for herself at home: little Florence Lubignac. Nor is it clear why my grandmother was chosen over her older sister; but Florence, a pretty, happy child with wide brown eyes and a gentle disposition was the one the Stanton women chose. My grandmother cried, begged, and clung to her grieving mother as she was handed over to Nanny Stanton; but giving up Florence would mean one less child for the struggling Lubignacs to feed and shelter, one child who would be provided for, however meager the provisions. Once in a while Florence received a visit from her family - she recalled her father once bringing her some clothes and a coat - but eventually the family fled Taylor for somewhere in Kentucky and Pierre Lubignac changed his name, probably to give the slip to his creditors. Florence never again saw her family, though she later learned that her mother fell into a severe depression and spent several years in a mental institution. So my grandmother, once loved and pampered, was plunged at 9 years old into a life of hard servitude. She was required to take care of the needs of the other children, do the laundry and hang it outside even in freezing weather, cook and scrub floors. She was allowed not one non-essential possession. Once Nanny Stanton caught her trying to curl her hair with a nail and took the nail from her. She was given what was left of the food after the others had eaten, and if there was some treat for the family it was not shared with her. It must be remembered that back in those days there were no child welfare or protection agencies; my grandmother was given to Nanny Stanton without any legal transaction or intervention on her behalf; she had no guardian; there was no record. According to my mother, the teller of my grandmother's story, "Back then children could be passed around like playing cards." As was my grandmother. When she was 17 my grandmother was sent out to get a job and was required to turn over every penny she earned to Nanny Stanton. But there was a young man from a wealthy family who became smitten with the young working girl and she with him. They wanted to marry but Nanny Stanton's heavy handed intimidation kept them apart. "He's too rich for you," she scolded my grandmother. But in truth there was another man, a relative of Nanny Stanton's, who had his eye on pretty Florence Lubignac. He'd seen the family's docile, obedient servant girl and decided he wanted her. And so my grandmother was given to Nick Fey. To be continued... Malaysian flight 370 has now been missing for 11 days and the desperate search for the plane and its 239 passengers has been taken up by 29 countries. Everyone of us on the planet is caught up in the mystery, captivated by it, we scan the news day by day, hour by hour for answers.

And though the news coverage is ongoing and constant, every answer that's given is linked to the greater question: Why? The plane turned around, but why? One or both of the pilots must have been involved in the plane's diversion, but why? The plane's transponder, which communicates the plane's location was deliberately turned off, but why? These"whys" have been swirling 'round and 'round, day after day, in the media and in our own minds, until finally yesterday morning New York times columnist Gregg Easterbrook thought to ask the most sensible "why", the one that should have been asked years ago, the one that, if it had been asked and appropriately addresssed, would have prevented the ordeal of flight 370. Easterbrook's question is this: "Why do airplane transponders still have a manual shut-off?" We've been hearing that the dismantling of the systems that communicate a plane's position is a highly technical proceedure. But apparently this is not true of turning off a transponder. According to Easterbrook, "Most of the world's jetliners have transponders that can be turned off...there's a simple rotary switch near the first officer's left hand. All someone has to do to turn the transponder off is rotate the dial". Easterbrook also writes that "...on September 11, 2001, one of the first things (the terrorists) did was to turn off the transponders, so the planes would not register properly on civilian radar...If the transponders had not gone silent on 9/11, air traffic controllers would have quickly realized that two jetliners en route to Los Angeles had made dramatic course changes and were bound straight for Manhattan. Instead, controllers lost precious time trying to figure out where the aircraft were." Easterbrook then asks why, after September 11, did it not become a requirement that all planes must be equipped with automated transponders incapable of being turned off? I'm sure those of us who fly frequently and have seen the seat size, aisle size and comfort level of planes decrease in direct proportion to the increase in the cost of flying could come up with our own cynical answers. But read Gregg Easterbrook's article. It's thought-provoking. And in view of what happened to flight 370, kind of infuriating. Find his article at: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/18/opinion/out-of-control.html?ref=opinion&_r=0 Though I believe myself to be as social an eater as any of my my fellow human beings, if you asked me which I preferred, a dinner party at Cameron Mitchell's or Smith and Wolensky or a snack of Combos and Diet Coke in my car I'd pick the Combos and Coke in my car.

Granted, that's mostly because I'm not partial to fancy expensive restaurants; on the other hand I do like eating Combos and Coke in my car. In fact of all the food I eat in my car the Combos-and-Coke combo is my favorite and the one I indulge in most often, almost every day, as I cruise from house to house, piano lesson to piano lesson. Combos and coke are my energy cocktail, what keeps my blood-sugar level steady (I mean, I'm guessing that's what it does) and my mood elevated at all times. As proof I'd challenge every student I've ever had over the last 17 years to come up with one instance when I've shown up for a lesson not in a good mood. Now you all know why. (Of course I guess it also helps that I like what I do, right?) Where Combos have it over my other car food choices is that you can pop Combos into your mouth safely while driving and then wash 'em down with a swig of your Coke at the stoplight. In truth I think it's actually sort of a freedom issue: cars give you the freedom to move around and Combos give you the freedom to eat while you're moving around. Not that there aren't a lot of other good freedom foods out there; and from time to time, depending on my mood du jour, I do feel like a bit variety in my driving-around menu. To this end I always keep, besides Combos, a substantial stash of similarly crunchy, salty, snacks in the console of my car. And of course even while driving around I do like my dessert, among my in-car favorites being gummy fish and caramels (though with caramels you have to wait for the stoplight to unwrap them. I think that's only responsible). Now I realize that confessing all this begs the accusatory rhetorical question: is that kind of eating healthy? I won't argue that it is. But my freedom food is my soul food. And if it's not keeping me healthy, well, at least it's keeping me happy. Eating. I notice I write about it a lot. Which must mean I think about it a lot. Does everybody think about eating a lot?

Eating is, after all, the thing we all do, we all enjoy doing, we all have to do to stay alive. It's the common denominator among us all: a shared need, a shared pleasure. In fact maybe it's our common need for nourishment that makes us social by nature. Maybe this is why we like eating together, why eating is at its best when it's done with others. Or at its worst. Depending on the others you're eating with. But even when bad drama is being served up and the menu is destined to go down in heartburn, social gatherings large or small usually include nourishment of some form. Which begs the chicken-or-egg question: Do we get together as an excuse for a having meal or do we have a meal as an excuse for getting together? But while we're all social eaters, we're all solitary eaters, too, some of us more than others, either by circumstance or preference. I'd venture to say that sometimes our circumstance becomes our preference. My own circumstance is such that I'm a frequent solo eater, usually at home in front of the TV or the newspaper or my computer, sometimes out at Panera or Tim Horton's or the various fast-food venues. In truth my favorite spot for a solitary nosh is in my car. I like to eat Kroger sushi in my car in the Kroger parking lot. I like to eat Walmart soft-pretzels with cheese dip in my car in the Walmart parking lot. When my daughter Theresa used to sing in the Columbus Children's Choir I used to take her to her Saturday morning rehearsal downtown and while I waited I used to like to drive over to the Parson's Avenue Krogers and eat a doughnut meal: a jelly doughnut for the main course and a cream doughnut for dessert, washed down with an ice-cold diet coke. (As you can imagine, back then I weighed 14 pounds more than I do now). The one frontier I've yet to conquer is to be able to walk into a sit-down restaurant by myself, order a meal by myself and eat by myself. I've thought many times about doing it - after all, I take myself to out the movies often enough - and I feel I'm at the threshold, but not yet through the door. It's not even that I've never done such a thing before; in fact, I've often eaten out in restaurants while traveling and feel perfectly comfortable doing so. While traveling. But it feels different when you're on your home turf. Which makes me wonder: do other people eat out solo around their own 'hood? I would like to try one of these nights when I'm hanging out with myself. I remember that when I lived in Paris, where eating out solo is (or at least was at the time) de riguer - that is, about everybody seemed to do it, even young people - there was a little cafe where I would go every day for lunch. I always ordered the same thing: un sandwich de camembert et un coca-cola, s'il vous plait. They knew me there. I think they were always waiting for me. It seems to me that that would likewise be the best approach for starting up an eating-out-solo agenda : find a place where it feels comfortable, go there all the time, become a regular. Maybe meet some other regulars. As a solitary eater I'm still evolving. But maybe I'll get there. |

"Tropical Depression"

by Patti Liszkay Buy it on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0BTPN7NYY "Equal And Opposite Reactions"

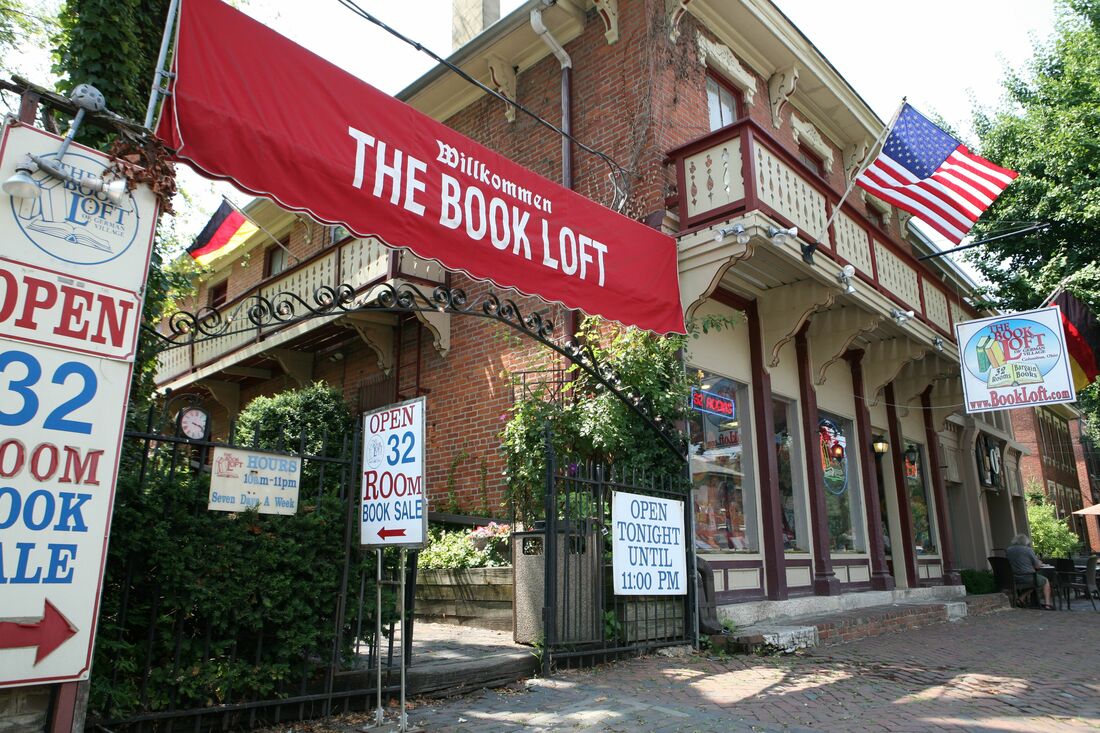

by Patti Liszkay Buy it on Amazon: http://amzn.to/2xvcgRa or from The Book Loft of German Village, Columbus, Ohio Or check it out at the Columbus Metropolitan Library

Archives

July 2024

I am a traveler just visiting this planet and reporting various and sundry observations,

hopefully of interest to my fellow travelers. Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed