|

It feels weird not to be able to email or skype my daughter Claire these days due to the lack of internet service in her quadrant of the Sierra Leonean jungle. But at least I can call her whenever I want, and relatively inexpensively since I discovered the existence of phone cards specifically for Africa. We're so used to being connected, wherever in the world we are. How different it was 40 years ago when I was living and working for the American Army in Aschaffenburg, Germany and state-of-the-art communication with family and friends States side was by letter. And it took at least a week or more for a letter to cross the pond. And while an overseas phone call was not altogether outside the realm of possibility, calling the States from Germany was a rare and expensive undertaking. In fact back then any personal call was for me a rarity, as I didn't even own or have much access to a telephone unless I could find - then figure out how to use - a local pay phone. At that time I was renting a small apartment on the third floor of the home of a German couple, Hedwig and Adolph. My quarters consisted of a living room with a bookshelf, table and a couch that doubled as my bed and a small kitchen with a bathtub in the corner. The toilet that I shared with another renter was out in the hallway. Now it so happened that there was in fact a telephone in my living room/bedroom, but there was a lock on it and so I always wondered why the phone was even there. So for all practical purposes I lived without a telephone. What this mostly meant to me was an inability to call in sick to work. Not that there was anybody to call, as I ran the post craft shop and my boss was some captain who worked in an office on a different post and I didn't have his number, anyway. I did, however call home to the States once during the three years I lived in Germany. It was an event. First I had to bicycle (my principal mode of transport) several miles to the Deutsche Bundespost, or German Post Office, located on one of the American Army posts in Aschaffenburg . At that time There were 3 posts in the town but only one of them (and not the one I worked on) had a Deutsche Bundespost. Upon entering the Bundespost I was directed to a small room that contained a couple of phone booths, a waiting area with several wooden chairs, and a desk at which sat the international operator who, thankfully, spoke English. I gave the operator the number I wanted to call and paid him in advance. I believe it cost maybe around two dollars a minute. (But remember, that was two 1975 dollars, back when the minimum wage was $2.10 an hour). The operator then advised me that it would take about 15 or 20 minutes to put the call through. So I sat and waited, brimming with excitement and anticipation, my stomach leaping when he finally called my number. As I recall, the connection wasn't that great, it was rather echo-y. But my parents and I were able to quickly exchange the necessary information. And that was the essence of my sole call from Germany to America. Then it was back to writing letters to stay connected. I guess we weren't as connected back then as people are now. I guess we didn't need to be so connected. Because we couldn't be. Now we can be connected to each other, any time, almost anywhere in the world. And because we can be connected, we need to be. They say necessity is the mother of invention. But I sometimes wonder if invention isn't the mother of necessity.

2 Comments

Sorry I didn't publish a post yesterday. It wasn't for lack of inspiration. Just lack of time. I had to let it go. It's been the better part of a week since we've received an email or skype from Claire, though when I stop to think about it, it seems extraordinary that I should expect instant communication with someone who's working in a jungle 4,881 miles from Columbus, Ohio. But in reality it's not at all extraordinary. Because even though Claire's clinic happens not to have any internet, nor do her lodgings at the Diamond Hotel, there are hotspots to be found at some of the other jungle clinics in the area, depending upon where they are situated in relation to the satellite. (Or whatever gizmo it is that delivers the WIFI). So if Claire had by luck of the draw been sent to one of the fortuitously situated clinics we'd probably be emailing or skyping every day instead of sporadically. But even though we can't skype or email, we could still have daily instant communication by phone if we wanted to. For about $1 a minute. The only problem with that option is that you're so distracted by the cost that the fleeing minutes and dollars end up being the focus of the call. It was Claire's husband Miguel who came up with the idea of looking for a pre-paid phone card for Africa that would hopefully lower the cost of a call. He'd been asking friends around Chicago if they knew of an African market or shop that might sell a phone card. Though such places surely exist in Chicago, none of his friends knew where to find one. But I did. Here in Columbus, and not far from where I live, there is a is a large African community. There are over 75,000 Somalians living in Columbus, along with many Ethiopians, Eritreans, Ghanans, and people of other African nationalities. The main East-West artery on the north side of Columbus is Morse Road, and if one were to take this road for about 5 miles west of my suburb of Gahanna, one would start seeing commercial establishments on either side of the street with names like African Paradise Restaurant , Dabakh Restaurant, Halal Market, Berekum African Market, Afric Market, Africa Euphoria Braiding, Jubba Travel Center. I often pass these places in my comings and goings, but had never thought to visit one until the issue arose of finding an African phone card. I knew that if a phone card was to be found in Columbus I'd find it in one of those shops. So last Friday I headed west on Morse Road until I came to the African commercial area. I randomly picked a promising-looking store nestled back in the corner of a shopping center: The store was small, with two rows of dry goods and a frozen foods area along one wall: At the back end of the store was a pallet piled with white woven bags of something - maybe rice or flour or some kind of powdered foodstuff - that looked to weigh about 30 pounds each. At the counter sat a friendly lady with a lovely lilting accent who told me when I asked that she was from Ghana. It turned out that she did carry several varieties of phone card that could be used to call anywhere in Africa and she asked me where I wanted to call and for what reason. I told her about Claire and explained that I wanted to buy some cards to send to her husband in Chicago. Most of the cards she sold required that the call originate in Ohio but she did have one card that could be used to call from anywhere: She told me I wouldn't have to send the card to Miguel, that I could just email him the numbers and instructions on the back of the card and he could use it right away. She told me to buy one and see how it worked for him. She charged me $4 for the card.

The card worked well enough, though, perhaps because of the torrential rain falling over the jungle at the moment when Miguel called Claire, the call was dropped several times and so they ended up with only 12 minutes worth of talk. But 12 minutes was 34 cents a minute, an improvement over the $1 a minute they'd been paying. So I went back to the Berekum Market and bought more cards, sent most of them to Miguel but kept a couple for myself. I tried calling Claire on my card and, this time the weather being agreeable on her end, we were able talk for 18 minutes without undue minute-dollar anxiety, during which time Claire assured me that she and her staff were doing fine and well though the work was intense. So soon I'll be heading back yet again to the Berekum Market. I think maybe this time along with more phone cards I'll buy something else from the store, some kind of food that I've never had before. I may also check out some of the other little stores and markets, maybe try an African meal at one of the restaurants. I suddenly find myself with an interest in all things African. ...And I thought to myself, This is why I love Peace. They know how to cover all the bases in a few words here. On the back of the challenge guide were a list of 20 spirituality exercises to choose from. I looked over the exercises, felt a surge of inspiration, and picked out five that I decided I would do: - Spend five minutes a day sitting quietly and paying attention to your breathing. Remind yourself that even your breath is a gift from God. - Attend an activity in which you are the minority (cultural, race, age, religion, etc). Listen. Experience. Appreciate. - Return that annoying grocery cart you almost hit as you pulled into your space. It's an act of silent service. - Connect personally (phone call or personal note) to encourage or console someone. - Practice the art of noticing. Spend time wondering what's happening in people's lives. Pray for them. I figured three of the five were were challenges more of an opportunistic nature, and that only two, the breathing and the noticing, would need to be practiced on a daily basis. I left church that day feeling as I often do upon leaving church, spiritually motivated and energized. Then I arrived home, tossed the challenge guide on the dining room table, ...fixed lunch, did some laundry, went grocery shopping, did some bills, practiced piano, fixed dinner, worked on my blog, and forgot all about the challenge.

Then yesterday afternoon I ventured back into that no-woman's-land in the dining room where I found my abandoned challenge guide and guiltily recalled my five forgotten resolutions. But re-reading the challenge guide was enough to re-spark my resolve, even if it meant being like the long-distance runner who ambles up to the starting line long after the gun has gone off and the others are on their way: On your mark...get set... Breathe. Notice. I love movies. I usually go to the movies twice a weekend with Tom, and before I started writing this blog I used to get in a couple of Netflixes or library DVD's a week besides.

I miss all that movie-watching. Too bad there's not an extra 2 hours in the day, then I could do it all. Or else just have another 2 hours to fritter away. Which is what some people consider movie-watching to be. Not me. I don't consider watching a movie a fritteration of time any more than reading a book is. To me the only difference between a movie and a book is that with a movie you cover more ground in less time. Not that some books aren't a whole lot better than some movies and vice-versa. And I'll even concede that there are probably more great books out there than great movies. But there are some great movies out there. This past weekend I saw one. I saw two movies, actually. One of them was great. So, on Friday night Tom and I drove across town to the Lennox AMC, which usually offers an arty/indy selection or two among the mainstream movie choices. We saw "Foxcatcher", a movie based on the true story of John Dupont, the creepy sheep of the mind-bogglingly wealthy DuPont family, and his weird involvement with a couple of Olympic wrestlers. All the movie critics loved this film. I thought it was like an excruciatingly long, slow, run-on sentence that you're thinking will never end then all of a sudden it does. It'll probably win an academy award. On Saturday night we returned to the Lennox to see "Cake". The New York Times hated "Cake." So did Rotten Tomatoes, Variety, Roger Ebert, and most of the other film critics. However the critic for the Associated Press loved it, and so did Tom and I. "Cake" stars Jennifer Aniston looking bloated, scarred, and miserable as Claire, a woman who went from having it all to having nothing except what money can buy. An accident has left her with a disfigured face and in constant pain. Because she's pushed away with both hands any one who cares about her she has no one in her life except for her long-suffering maid. Claire is the one patient that no doctor, psychologist or physical therapist can tolerate: the patient who doesn't respond to treatment, whose condition doesn't improve, who doesn't heal. In the opening scene of the movie Claire is kicked out of her pain support group for a purposely insensitive comment she makes regarding Nina, a member of the group who recently committed suicide. But Claire becomes obsessed with Nina, and in her percoset-popping, insomniac existence imagines Nina visiting her from the other side from time to time, always looking fresh, lovely and pain-free. Claire develops an approach-avoidance fascination for suicide and for Nina's widower husband who understands that Claire is suffering intensely on a deeper level than what she feels physically. All the characters in "Cake" tugged at my heart: suffering Claire, her kind-hearted maid, the broken-hearted widower, the people who seek to help Claire, the people she pushes away, the ones she finally reaches out to. I loved every character. Every character resonated with me. I sniffled my way through the movie and sobbed at the end. I don't think "Cake" will win any academy awards. But it really moved me. My brother Joe wrote this comment in response to my 1/20/2015 post, "Where Have All The folk Songs Gone?": "The folk songs have gone the way of all other things. It is much harder to be a kid these days. Back in the day, on average, everyone had it fairly good. There was time between classes to smoke a joint. Now the kids have to smoke a joint to get through the day. Although I am out of touch, it does not appear to me that there is a "privileged" generation out there as we were. I do not believe social awareness is present as it once was. It is just too hard for the younger group to get through the day." I think Joe has a point. The college students of our era enjoyed a sense privilege that had less to do with material affluence than confidence in the wide open door of possibility before us. Many of us were the first in our family's history to attend college and that, too, gave us a feeling of privilege in the knowledge that we would be more educated and likely more successful than our parents. And we didn't arrive at college already fretting over what major would make us the most money and with our souls shackled to the knowledge that the price of our degree would be a lifetime of debt. In fact those were the days when it was still within the realm of possibility to work one's way through college. As Joe noted, we had it fairly good. And we knew we had it good, that we were privileged. And so, unencumbered by a financial yoke and feeling secure in our present and our future, our material needs provided for, we had the werewithal to care about greater issues. We were primed for the great social awakening that took place during our time. I agree with Joe that youngsters today are less socially aware because times are harder for them than they were for us. They live in an age of anxiety over their own situations and futures and so can hardly be expected to care about issues and problems afflicting the rest of the world. And yet some of them do anyway. Tom pulled up a satellite map of Yengema, where Claire now is, in the Kono District of Sierra Leone, and here's a section of what came up: A bigger view showed more of the same, vast areas of green broken up by vast areas of brown.

We're guessing, based on Claire's description of the landscape around her, that the green must be the jungle and the brown the diamond mines. We've received little news from Claire over the past few days, only a few lines in a brief email mostly assuring us that she is safe and well, and a phone call from Miguel to tell us that he'd talked to Claire for a few minutes and she'd relayed as much. We did learn, though, that she's been working this week in a community care center in the jungle, coordinating the triage operation and serving as a clinical mentor to the local nurses in critical care skills. Claire says the Sierra Leonean nurses are so nice and full of enthusiasm, they call her Sister Claire or sometimes Kumba, which means her parents' second daughter. The care center is very small and has only 12 beds. If it's determined that a patient has Ebola they'll be cared for until they can be transferred to the closest Ebola treatment unit, which is about an hour away over treacherously rough roads. At the end of this week Claire will be transferred to the government hospital in Koidu Town, the capital of Kono District about 30 miles from where she now is, where she'll probably continue with the same duties she's now undertaking. Claire works at the care center from around 8 am to 6 pm, going throughout the day in and out of the Hot Zone, or the area where the Ebola or suspected Ebola patients are. After work she comes home to the Diamond Hotel for a hot shower once the water comes on, dinner, then maybe a pick-up game of cards around the dinner table with some of the other Partners In Health staff. Claire works every day, though she says could probably have a day off if she needed one. Which I guess begs the question: what would she do with a day off, anyway, in an area under siege from Ebola? Yesterday morning I was sitting at my regular spot in Coffee Time (see post from 10/28/2014). Anyway, I was working on yesterday's blog about how back in my day young people used to sing and play the guitar. And as I wrote, lost in memories of the music of my youth all those years ago, I could actually hear guitar music. No, I mean, I actually could hear guitar music. I looked up from my laptop and there behind the counter stood the young barista strumming a small Spanish guitar. "Oh wow," I exclaimed, walking over to the counter, "I was just writing about how mine was the musical generation that just pulled out guitars and started playing anywhere, and here you pull out a guitar and start playing!" We began chatting, and the friendly barista, whose name is Tommy, assured me that his generation loves their music as much as mine loved ours and that young people still do get together to play and jam, as he does with his group. He pointed out, though, that our generational styles were very different, as folk music that people back in my day played was more acoustic (not electrically enhanced) while his contemporaries tend to dabble in producing electronic techno sounds, such as dubstep (pop music made up mostly of repeating drum rhythm and a bass line - you'd know it if you heard it) and electronic dance music. He admitted that a group of people sitting around singing while someone strummed a guitar would be more rare. Then he played some of his music for me. It was neither techno-pop nor kumbaya-style strumming, but beautiful flamenco-style classical guitar pieces that Tommy had composed himself. I was impressed by his playing and asked him if he'd studied guitar for a long time. He said that he'd taught himself to play from the internet and from books. And from many hours of practice, I thought to myself. As this was the first time I'd ever seen Tommy at Coffee Time or heard him play I asked him if his playing might become a regular attraction here. He said he does bring his guitar with him to work at Coffee Time, but that he mostly plays evenings over at Three Creeks on Mill Street at Creekside in downtown Gahanna. Three Creeks is also owned by Coffee Time proprietor Sally Held. In fact, if you're in the mood for some lovely live music Tommy and his Spanish guitar will be at Three Creeks tonight, Wednesday.

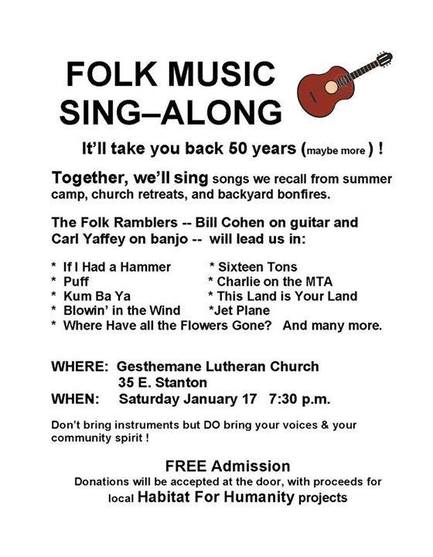

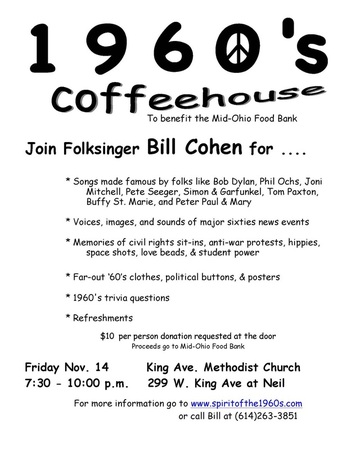

It's open 'til 8:00 pm. A couple weeks ago while at Panera with the Posse I saw tacked to the restaurant's community announcement board this flyer : ...and thought, "Okay, I am so doing that!" When I told Tom about the sing-along he was immediately on-board, as I knew he'd be. Tom, like me, is a big fan of Bill Cohen, the folksinging former Statehouse reporter for Ohio public radio and television known for his cool, soothing voice and his annual 1960's Coffee House: ...which Tom and I seldom miss, being among the baby-boomer generation who came of age in that wonderful era known as the 60's, ....with all that great folk music. Maybe it wasn't even that folk music was all that great. Maybe what was great about it was that it was singable. And that we all of my generation sang it. And last Saturday a few hundred of us were singing it again. I couldn't get over how old we all were. "We're the youngest ones here," Tom observed with amazement in his voice. Though we probably were not actually the youngest, Tom wasn't far from wrong. But when we started singing the good old songs we were suddenly transported from looking like this: ...back to those days when we looked like this: Here's what was rather amazing about our sing-along: There were no song sheets. "You won't need any song sheets," Bill Cohen had told us at the beginning of the event, "trust me, all the words of these songs will come right back to you." And he was right. Forty, fifty years later, we all still remembered the words to these songs. Over the two hours we were there Bill on the guitar and his banjo-playing duo partner Carl Yaffey, ...played 21 songs and I remembered almost all the words to every one, except for one song called "Passin' through" which neither Tom nor I had ever heard of and which nobody else seemed too familiar with. Tom thought the guys might have made that one up. But the other 20 songs, we knew them all. That's how much we loved those easy-to-sing songs and how much we used to sing them.

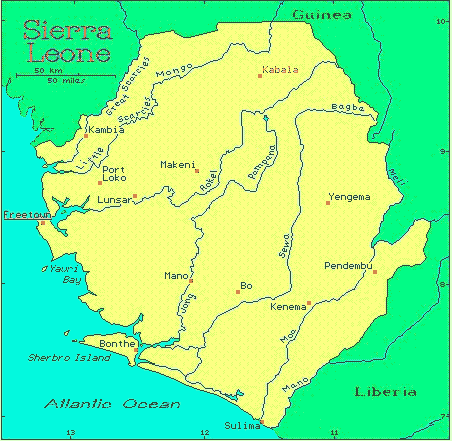

But they were more than songs to us. They were our statement, our protest against war and the establishment and materialism, our proclamation of our desire and belief in a simpler lifestyle and better, more just and equal society. Young, unencumbered, well-fed idealists that we were. I remember a spoof by 60's singing satirist Tom Leher called "The Folk Song Army" which had a line, "We are the folk song army, in our march against poverty, war, and injustice: ready, aim, sing!" And sing we did. Back when I was in college from 1969 to 1973 every other person played the guitar, me included, though I actually learned because I had a part in a play my sophomore year and in one scene my character had to play the guitar while the other person sang. When I told the director that I didn't know how to play the guitar he waved his hand dismissively and said, "So, learn. Teach yourself. Have somebody show you." And that was exactly how we all learned the guitar back then. We taught ourselves and we taught each other. The commonest sight in the world on a college campus back then was somebody sitting under a tree or on a bench practicing guitar alone or with another, maybe singing, alone or with a group, singing and playing the same C - A minor - F -G seventh chord pattern of the folk songs that we all knew. "That's what young people used to do back then," Bill Cohen reminded us at one point in the program, "someone would pull out their guitar and we'd sit around and sing. (Sigh). Indeed we did. And indeed, given the opportunity, we of the Folk song Army, though now retired, still will. (N.B.: Again I was late with Friday's post, which I didn't get out until Saturday. So if you missed "Port Loko", just scroll down from today's). On Saturday I received a call from Claire's husband Miguel. Miguel at the La Fleur orphanage in Haiti during a medical mission trip last October. (See post from 10/24/2014) Miguel had spoken briefly to Claire, just long enough to get a few snipets of information, mainly that she had arrived safely in Kono District from Port Loko. As it turned out the trip took only 6 hours, not the potential 11 hours, but it was a hard 6 hours all the same as the roads were so rough and rutted that Claire and her travel mates -3 others came with her from Port Loko - spent most of the trip being thrown about and against each other in the truck in spite of seat belts. When the team finally arrived they were shown to their quarters at the Diamond Hotel - aptly named, as Kono is the location of Sierra Leone's diamond mines. Claire learned that the Diamond Hotel is owned by Russians and that Paul Farmer has rented out the whole hotel to house Partners In Health medical workers. She told Miguel that it's a beautiful hotel - there was hot water and electricity when she arrived but unfortunately no internet - and that she thought that this location may be her permanent assignment while she's in Sierra Leone. And that was all Miguel could tell me. I tried doing a bit of internet detective work to see if I could put together a little more information about where Claire might be and what might be going on there. I started by googling "Diamond Hotel in Kono, Sierra Leone." I found nothing at first - the hotel apparently has no web page - but after scrolling around a bit I came across a publication put out by the State House Communications Unit of The Republic of Sierra Leone on November 25, 2014 entitled, "Enforce the Bye-laws to Eradicate Ebola, President Koroma urges Kono Chiefs". Within the article was the following text and photo: "The issue of the role of paramount chiefs and religious leaders in the fight against Ebola was once more the focus of the town hall meeting held by President Ernest Bai Koroma with Kono stakeholders at the Diamond Hotel auditorium, Yengema, in the eastern diamond rich district of Kono". ...from which I deduced: 1. This must be a photo of the auditorium of the Diamond Hotel where Claire is staying. Unless the Diamond is a chain of Russian-owned hotels in the Kono district, which would blow my whole deduction, but assuming there's only one Diamond Hotel and it's located in Yengema, then 2. Claire must be in Yengema. I tried to locate Yengema on a map but couldn't find it marked anywhere. In fact all I could find out about Yengema was this from Wikipedia: "Yengema is a diamond mining town in Kono District in the Eastern Province of Sierra Leone, lying approximately 30 miles from Koidu Town (the largest city in Kono District), and about 260 miles east of Freetown. The major industry in and around Yengema is diamond mining. The town is home to Yengema Airport, the main airport serving Kono District. The population of Yengema was 3,621 in the 2004 census and a 2012 estimate is of 13,358 people.The population of Yengema is largely Muslim." I also learned after some internet research that Kono District appears to be the up-and-coming Ebola hotspot, but that it's been hard to assess because there are no Ebola treatment units in the district yet, only local clinics to treat the sick. But the numbers of sick and dying in Kono have been on the rise. And so I expected that's why Claire's team has been sent there. As it turned out the opportunity popped up yesterday, Sunday, morning for Claire and I to Skype again. It was afternoon for her, as Sierra Leone is 5 hours ahead of us, and several staff members including Claire had traveled during their work break from their clinic to a another nearby clinic where it was rumored that there was internet. The rumor turned out to be true, and so Claire and Tom and I were able to skype, though without any video, as the video would eat up too much charge on Claire's iphone, which she wouldn't be able to re-charge until after work when the electricity came on in her hotel that evening. I asked her if she was, in fact, now in the town of Yengema. Claire didn't know exactly where she was. All she knew was that she was about half an hour outside the city of Koidu (which reminded her of a much smaller version of the city of Leon, Nicaragua), in what she described as "the outback of West Africa". Her hotel is close to the diamond mines and she's seen the workers entering the mines with their picks.

Though the Ebola epidemic has shut down most of the country the diamond mines are apparently still up and running. Anyway, Claire's hotel is, in fact, the same Diamond Hotel mentioned in the above article. She described it as a "palace" used by the "diamond heads", as she called the diamond magnates, when they came to visit the mines. She has a beautiful private room with a huge bed and for about 12 hours a day there's running water, electricity, and air-conditioning, but no internet. Claire will be working as a clinical mentor in a community care center staffed by local nurses. Her job, among other duties, will be to help the nurses learn how to effectively triage suspect Ebola cases, treat them if they in fact have Ebola or send them elsewhere if they don't. She'll also try to determine what their educational needs are and what they would like to learn. Claire says everyone is so nice, the Sierra Leonean nurses are lovely and enthusiatic and call each other "Sister". And so Claire is "Sister Claire." There is heavy security everywhere, soldiers armed with rifles and pistol-shaped forehead-scanner thermometers which they don't hesitate to use (the thermometers, not the rifles). Claire said during the trip from Port Loko to Kono District their truck was stopped at least a dozen times by soldiers for temperature screenings.

And so Claire says she feels safe and in good hands and all has been well with the exception of one harrowing experience the night she arrived in Kono. She was getting ready to go to bed and decided to open the window as the air conditioner was on down time. As soon as she opened the window a small winged worm-creature flew into her room, headed straight for her bed and zipped under her bed sheet as if that were his planned destination. Claire calmly procured a glass from the bathroom, carefully pulled back her bed sheet, deftly trapped the worm in the glass, escorted him to the window, gently dispatched him out the window, then slammed the window shut, ran to her bed and whipped the mosquito netting over her bed like a house afire. As Indiana Jones would say, "Why'd it have to be flying worms?" Yesterday, Friday, I heard from Claire again. We skyped for about 40 minutes, taking advantage of a fleeting episode of on-again, off-again electricity and WFI in the building where she was staying. Anyway, Claire and her Partners In Health team left Freetown, Sierra Leone, on Wednesday for the Ebola treatment unit in Port Loko, a rural area about 2 hours northeast of Freetown. On the way to Port Loko they passed through many checkpoints, mostly made of wood and rope, and they were stopped by police and soldiers for for a health screening at each town they entered. Upon their arrival in Port Loko some team members were assigned to a tent city set up by the Danish military while others, Claire among them, were assigned to an all-pink night club and hotel called The Sugar Sharg closed by the Ebola epidemic and now used as accommodations for medical staff. The view of the town of Port Loko from Claire's hotel. She said there are sheep and goats crossing the road at all times. During our Skype session Claire walked around with her computer to show me her accommodations: her bright-pink hotel room and bed canopied with mosquito netting and her "shower", i.e. the two buckets she fills with well water from a pump out in the court yard then hauls back into the bathroom, then standing over a drain in the floor, scoops up water from the buckets and dumps it on herself. Ironically, the Danish tent city has hot water, showers, electricity and WFI 24/7, though the residents must leave their tents to get to the bathroom. To which I responded, "Eh, like on the Camino sometimes." (See Tighten Your Boots", my daily blog of Tom's and my hike over the mountains of the Camino de Santiago de Compostela in Spain last year). After the tour of her room Claire walked outside with her computer to show me around the grounds a bit. She ran into a couple staff members, Eliska, the woman who runs the hotel and Muhammad, one of the two hotel security guards (both named Muhammad). Claire introduced us via Skype. Eliska, a nice-looking middle-aged lady, was very friendly and gracious and promised to take good care of Claire. While Eliska spoke English, the official language of Sierra Leone, Muhammad spoke only Krio, the country's native tongue, a mix of English, French, Portugese, and the African Yoruba an Igbo languages. Still Muhammed, dressed in a white tee shirt, jeans, and a red baseball cap, was friendly and showed me the hotel's well and water pump, and gave a demonstration on how the pump worked. They were nice people. How amazing that people from opposite sides of the world can connect through a video screen. Claire also showed me several pairs of scrubs - what the doctors and nurses wear under their Ebola hazmat suits - washed and hung out to dry on the barbed wire atop the hotel wall. After my tour Claire and I talked a while longer. She's now had two days working in the Ebola treatment unit. I asked her how it was wearing the Ebola gear and she said that the first time she put it on after 20 minutes she felt so hot and woozy that she was truly feared she was going to faint and wondered how in the world they'd ever get her out of her gear. However, she made it through the required hour in the suit and then the twenty minutes it took to get her out of the suit. She chalked her faintness up to dehydration - she drank 3 liters of rehydration salts after leaving the suit. Yesterday she made sure she was well-hydrated before putting on her gear and did better her second time. To prevent over-heating and dehydration a person can only be in the Ebola suit for an hour at a time - plus the twenty minutes it takes to be de-suited. A few hours later the person can then get suited up again and return to the Ebola treatment unit for another hour of work. The Partners In Health team members work along side local staff hired by PIH, hygienists who keep the unit clean, nurses, translators, and sprayers who follow the teams around spraying them and everything else with chlorine. PIH also hires Ebola survivors to help around the unit, especially to be with the sick children who are there without their parents. Claire said seeing the survivors caring for the children did her heart good. She said there were about 200 staff members working 'round the clock in the unit. As most of Serra Leoneans are Muslim, there is a prayer hutch on the unit where people stop during the day to pray. Claire also shared that she caught a glimpse of Partners In Health founder Paul Farmer. He stopped by the Ebola treatment unit and waved through the fence at the team all decked out in their Ebola gear. Claire said she stopped and waved back. Claire learned yesterday that today she will be moved to the Kono district, in the mountainous jungle region on the eastern border with Guinea where the country's diamond mines are located: There is no Ebola treatment unit yet in Kono, only community care clinics, some run by the Red Cross, that have been transporting their suspected Ebola patients to treatment units many hours away. Claire is not yet sure what to expect when she arrives.

Normally Partners In Health transports their team members from spot to spot by helicopter, but as today is Saturday and the next helicopter flight isn't until Monday Claire will be making the 11-hour trip by truck. She is most likely making that journey at this moment, as I write. |

"Tropical Depression"

by Patti Liszkay Buy it on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0BTPN7NYY "Equal And Opposite Reactions"

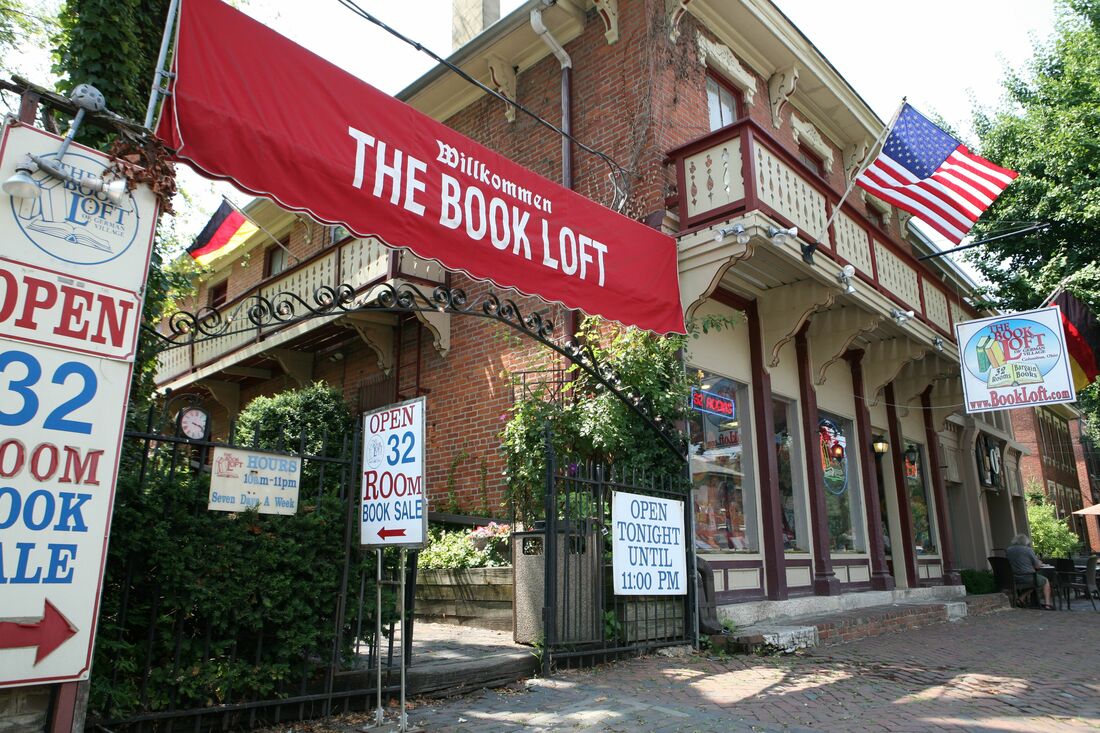

by Patti Liszkay Buy it on Amazon: http://amzn.to/2xvcgRa or from The Book Loft of German Village, Columbus, Ohio Or check it out at the Columbus Metropolitan Library

Archives

July 2024

I am a traveler just visiting this planet and reporting various and sundry observations,

hopefully of interest to my fellow travelers. Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed