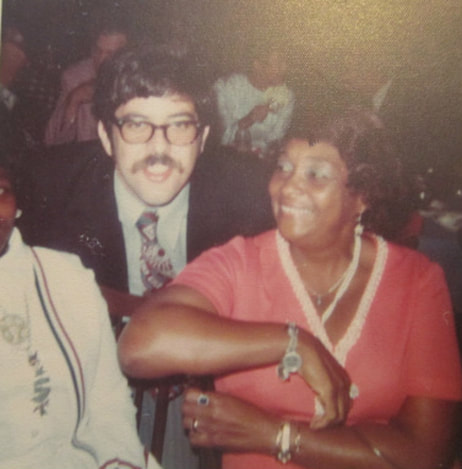

My brother Joe clowning around with Barbara at our parents' 25th wedding anniversary  And with Ann I think I was around 6 years old when I heard the word for the first time being bandied around by some older boys in the long wide concrete alleyway that ran behind our block of row houses and divided our block from the next block and served as our community playground. I went home and ran the word by my mother, who locked my heels on the spot and warned me never to use that word again, that it was a very bad word, and how that word would hurt Barbara, Barbara's husband PS and her sons, Robert and William, who were the lights of her life. That word would also hurt Barbara's friend Ann who sometimes came over with her, as well as Ann's daughter, a little girl around my age whom I'd played with a time or two. Did I want to hurt Barbara?, my mother asked. No, I replied, feeling guilty for even having heard the word. Then, said my mother, I was never to use that word. Ever. And I never again did. Ever. (To this day I cant' bring myself to say the word, or even to write it in this blog. Which is not to say that I'm not capable of belting out one or another of all the other bad words on those rare occasions when one of those words might be warranted. Just not that word). And though you'd think I'd have learned my lesson from my mother's reaction to my first and only use of that one word, I continued to come to her for guidance on the truth of other negative racial stereotypes as I heard them. And always she set me straight with the same question: How would Barbara feel if she heard you saying that? Do you want to hurt Barbara? So I leaned at an early age the consequences of subscribing to racial sterotypes: They could hurt Barbara. And, by extension, my mother. Because I knew that my mother loved Barbara. Though at the time it was nowhere on my young radar, I look back now at the improbability that in the 1950's a white doctor's wife and her black household helper could have been best friends. I look back with even more wonder at how they worked their friendship around the employer-employee situation; though maybe it was just one of those very auspicious situations where each party was so equally satisfied with the work-for-pay transference that it just never became an issue between them. Or maybe Barbara and my mother were just two friendly, outgoing, funny women, one the daughter of a washer woman from Scranton, Pennsylvania and the other a farm girl from Georgia who were so drawn to each other's hearts that they just naturally slid by the obvious obstacles of race and social standing.  Barbara and my sister-in-law Debbie at my wedding  My brother Jimmy dancing with Ann at my brother Joe's wedding Barbara died about 25 years ago of Altzheimer's . By then it had been many years since she and my mother been in a business relationship; now they were just two old friends, one grieving for the other who was slipping away. I believe Romaine was the last among us siblings to see Barbara before she died. She told me the story of how one night she was sitting in her house during a storm and she kept hearing a light tapping. Though she assumed the tapping must be a tree branch, she went to her door and looked out the peephole and saw Barbara standing there wearing a beautiful green and gold turban. She pulled open the door but there was no one there. She called my mother and told her about the vision, and my mother was convinced that Barbara was trying to send Romaine a message that she wanted to see her. So the next day Romaine and my mother drove over to visit Barbara at her home where PS still cared for her. Though she didn't seem recognize Romaine or my mother, they all sat together on the sofa for a while. That was the last time Romaine ever saw Barbara. The last time I saw Barbara she still knew who I was. I was in for a visit from Ohio, and all I remember of our last conversation was that I was showing her an afghan I was crocheting made with a big broomstick loop. Barbara liked the broom stick loop so much that she asked me to make her a sweater of the same texture. I told her that I didn't know how to make a sweater, that all I could crochet were scarves and afghans, but that I'd make her a scarf or an afghan. Or both. I offered to let her have the one I was working on when it was done. But Barbara wanted a sweater. She was sure, she told me, that I could make her one, so I told her that I would. But I never did.  My broomstick loop afghan that Barbara wanted made into a sweater

1 Comment

Romaine

5/14/2014 07:39:51 am

Great pictures! This blog makes me a little sad. There are so many things in life I wish I could back and change too.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

"Tropical Depression"

by Patti Liszkay Buy it on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0BTPN7NYY "Equal And Opposite Reactions"

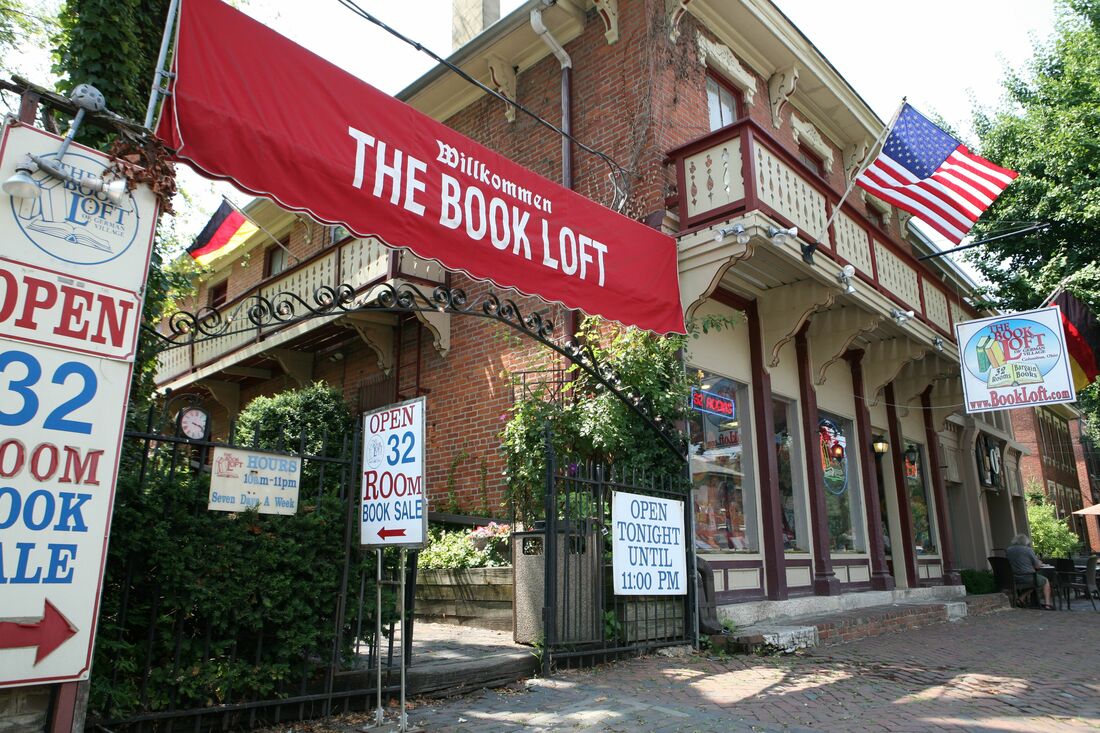

by Patti Liszkay Buy it on Amazon: http://amzn.to/2xvcgRa or from The Book Loft of German Village, Columbus, Ohio Or check it out at the Columbus Metropolitan Library

Archives

July 2024

I am a traveler just visiting this planet and reporting various and sundry observations,

hopefully of interest to my fellow travelers. Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed