|

My daughter Claire is currently in Bangladesh with Medglobal giving medical care to the Rohingya refugees from Myanmar (see posts from 1/3/2018, 1/4/2018 and 1/5/2018).

Claire is doing well, if exhausted at the end of each long day of treating endless lines of very sick children and adults. A few days ago she sent me the following piece that she wrote and some pictures, which I'll now share with you: Cox’s Bazar is a lovely resort town in eastern Bangladesh known for its 125-mile-long beach, the longest beach in the world. Cox’s Bazar has recently become the destination for the 800,000 to one million Rohingya refugees who have fled Myanmar after being tortured, murdered and driven across the border by the Myanmar military. This morning I ride in a van with my fellow MedGlobal volunteers who are here for the same reason as me: to provide primary care to those living in the refugee camps outside of Cox’s Bazar, near the border of Myanmar.

We drive through rice paddies and see the local Bangladeshis hunched over in the fields. We reach the edge of the camps and pass by the food distribution points as refugees wait in the sun for their allotment of food.

The MedGlobal clinic is on the edge of the Balukali camp. I know that the patients will be lined up and waiting for us when we arrive, as they always are. The waiting area has benches for about 100 waiting patients. Those without a seat will squat in the shade as they wait outside.

I walk into the clinic and am immediately directed to the procedure room by the local midwives, who have been registering patients while waiting for us to arrive. A young woman is lying on the stretcher, moaning and dry heaving. The midwife tells me that her blood pressure upon arrival was 60/40. I feel for a pulse, which is rapid and weak. I grab the blood pressure cuff and take another pressure. She does not have a blood pressure in her right arm. “No pressure” I tell the field coordinator and the doctor in the room with me. I try the other arm. No blood pressure there either. I prepare to start IV fluids and the doctor begins the process of learning the patient’s history through the interpreter. She has been having diarrhea and vomiting for the past several days. She’s gone 12 times today already. She hasn’t urinated since yesterday. She starts to vomit and I sit her up. She loses consciousness so I lay her back down and turn her head to the side. The field coordinator is on the phone with the field hospital about 25 minutes away to see if they will accept the patient. The local transportation coordinator readies the ambulance, which is really a van with a bench and a siren.

I apply the tourniquet and begin looking for a vein to start IV fluids. Her veins are small and she is massively dehydrated. What she needs is an ICU I think. She needs a central line and vasopressors to bring up her blood pressure. She needs to be placed on a ventilator. She needs IV antibiotics. Nutrition. Clean water. A roof over her head. A secure place for her children to grow up. After two tries I place a tiny IV in an impossible vein. I start the IV fluids and the field coordinator gets the OK to send her to the field hospital. The patient’s husband gently lifts the patient from the stretcher and carries her to the ambulance. The doctor rides with her in the back. As the ambulance pulls away I look around me. Several Rohingya children have made kites out of trash and are busy flying and chasing them around outside the clinic. They shriek and giggle as the wind blows the kites into the trees. I walk back inside and see 100 eyes watching me. Tired eyes, hopeful eyes, eyes white and blinded from years of vitamin A deficiency.

As I have been working a line of patients has formed who have been sent to me for various treatments. Some need nebulizers, some IV fluids, some a shot of antibiotics. A few need additional testing for malaria, UTIs, pregnancy. Others need wound care for countless traumas suffered at the hands of the military, or while struggling up and down the dirt cliffs of the camp. I start with “Ken Acho,” a Rohingya greeting for “How are you?” My poor attempt at speaking Rohingya gets a smile from a few of the waiting women, the intended response. We get to work.

4 Comments

Rikke

1/15/2018 05:55:54 am

I have no words . My best attempt: I believe your daughter and others like her Are true saints. Such selflessness and courage.

Reply

Patti

1/15/2018 06:13:38 am

Oh, thank you, Rikke. You know, I'm just thinking about how it was that we just happened to run into each other on the Camino for a moment - I think I snapped a picture of you and Betty and then a little down the road you snapped one for Tom and me and now we're long distance friends who follow the events of each others' lives. Say what you will about Facebook, I think it's a good thing!

Reply

S

1/23/2018 03:14:15 am

I worked with Claire at the Medglobal Rohingya clinic. Her clinical acumen and passion to her work is amazing. She was dependable and I felt confident passing on my patients to her for intervention. Great write up, Claire.

Reply

Patti

1/23/2018 04:59:29 am

Thank you so much for your kind words, S. I know that you, too, are doing wonderful and praiseworthy work in your care of the sick and vulnerable at the Medglobal Rohingya clinic. Thank you for your work.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

"Tropical Depression"

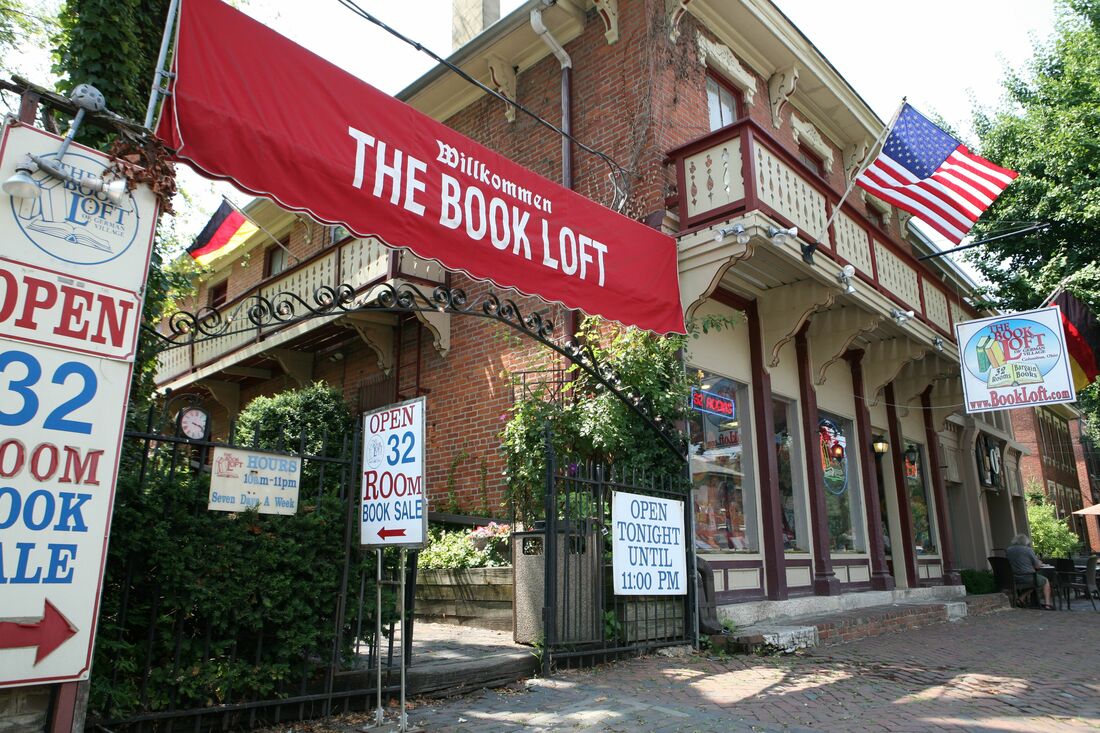

by Patti Liszkay Buy it on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0BTPN7NYY "Equal And Opposite Reactions"

by Patti Liszkay Buy it on Amazon: http://amzn.to/2xvcgRa or from The Book Loft of German Village, Columbus, Ohio Or check it out at the Columbus Metropolitan Library

Archives

July 2024

I am a traveler just visiting this planet and reporting various and sundry observations,

hopefully of interest to my fellow travelers. Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed